Old collections and new media

How do you get modern inspiration from historical artefacts? How to unravel the thick of time in a fun way? Perhaps browsing this site will allow to start with these questions and combine old artefacts with new media to give us some sparks of thought.

about project

What's the Old

and New?

Combining historical data itself and new media technologies to examine what the kirkgate market is telling us today. Also show the ways in which we can study historical data through the use of new media.

Pictures First

Are these familiar

to you or not?

Research Start

literature review

Data, New Media and Historical Collection

When it comes to data, the most important first thing should be to clarify the definition of data that we have used in this study. In all current research, data are basically divided into two categories, one related to the data itself and the other related to computers. The former defines data as factual information used as a basis for reasoning, discussion, or computation (H. A. Gleason, Jr.), while the latter, in joint computer terminology, defines it as information that has been converted into a form that can be moved or processed efficiently. Or: information converted into binary digital form (Jack Vaughan). It is easy to see that, in any case, data is information of some kind. And this coincides with the meaning that will be adopted into this study.

So as some kind of information, how is new media technology utilised in the data processing process in modern research into history? What are its negative effects?

In practices related to new media, most historians use word processors and conduct online searches as a regular part of their research, but they also make extensive use of other applications and tools, including digital scanners and cameras, as well as a variety of other programs used to organise material and process data (Robert B. Townsend). In addition, the findings of related studies occur mainly in the field of museum and heritage studies. Some experts argue that digital resources mobilised by cultural heritage institutions, such as museums, are presenting artefacts and history from an increasingly diverse range of perspectives, presenting a multi-sensory combination of content that is difficult to capture and present in other forms (Jenny Newell). Another segment of experts sees such data as memory ecologies built for history, offering them more interactive possibilities through multimodal platforms and social media applications (Brant Burkey). In other words, in historical research artefacts and cultural heritage are stored in databases in a datamaterialised form and presented in multiple forms and modes of interaction through new media technologies.

With regard to the negative aspects, current research seems to take into account mainly the characteristics of the data itself. On the one hand, the "authority" of the data itself makes it difficult to question, and with that comes the limitations to critically examine it (Jonathan W. Crocker).

On the other hand, Big Data has been studied as a subject, and it has been argued that Big Data acts as fictional data, and is therefore powerful in constructing an understanding of historical data and the possibilities it offers (David Beer). It has also been argued that big data is in some cases ignoring history due to, for example, the explosion of information, and that this can create a crisis. (Trevor J Barnes). At the same time, the role that new media plays in confronting people with historical data has been criticised by some scholars, with some arguing that it creates a false data utopia. And this can only be addressed by developing people's critical thinking (Greg Diglin).

This project aims to analyze the narrative data about Kirkgate market by using the methods of new media, the data can reflect the development of Kirkgate market, the project also learn the history about Kirkgate market through big data such as the websites and online literatures. Using big data is a good way to learn the issue that is in the past, because the qualitative data that is collected through the method of big data is longitudinal, and it is helpful to learn the subject that is changed over time (Bail, 2014). Using big data is an important way for us to learn the development of Kirkgate market through the history as there are a few resources that demonstrates its refurbishment and communication meaning to people in the past. Through the reflection of data, the project can learn the advantages and limitations of Kirkgate market when it tries to adapt to the new era and simultaneously keeping its classic features.

As well as providing affordable food to a diverse community, Kirkgate Market in Leeds is also an important social space that provides inclusion to the community. Market traders and customers also practice cultural exchange and adaptation during the trading process, promoting intensive socializing and interaction of different backgrounds. And raised concerns that recent reforms to Leeds City Council may have raised concerns about the gentrification of the market and the loss of sociability in the field (Rivlin and González, 2017).

Advantages in being classic traditional market with popularity

Kirkgate Market is a classic market that symbolizes the culture of Leeds, it has kept its traditional feature for so many years and it is still popular among local customers. There are several reasons that could explain its popularity and it does have some irreplaceable advantages.

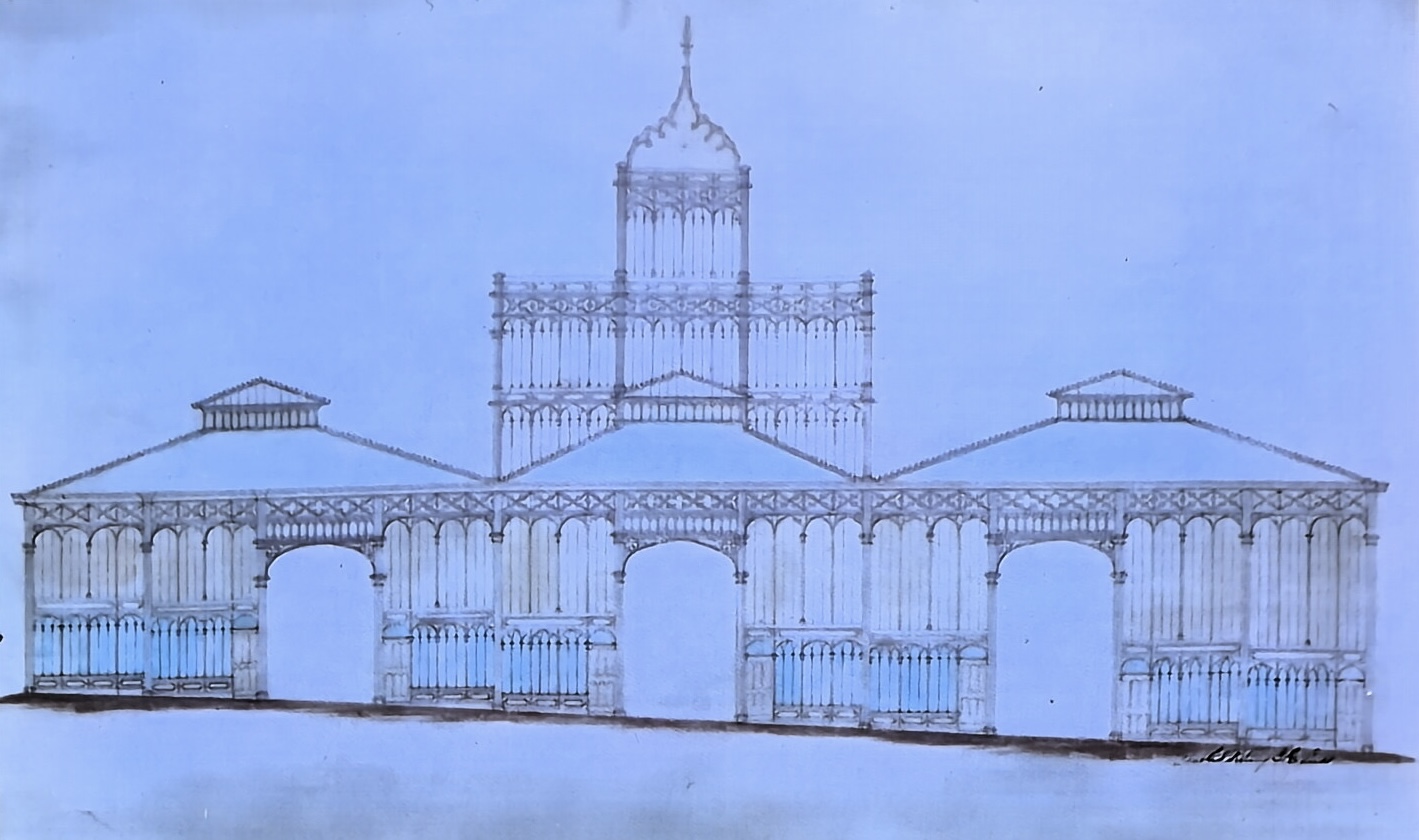

First, it has historical and cultural value. Kirkgate market is one of the largest covered market, it used to be a collection of livestock, corn and street markets, and it was built to be a covered market in 1857. Its central location in Leeds made it an important social landmark, it was also the key public interactive space for integrating urban strangers, new residents to the city and migrants, so it facilitates communication across national, ethnic, linguistic, religious, and socioeconomic differences (Rivlin and González, 2017).

Second, shoppers can usually get a variety of items with nice quality and reasonable price, and many items in Kirkgate market are exclusive. Kirkgate market is the biggest and most diverse retail outlets in Leeds. The items include vegetables, seafood, meat, flowers, stationary, curtains and many other items (Gonzalez and Waley, 2013).

Third, the market is keeping much of the humanised feature of trading habits which only old market has. It is keeping its old-fashioned but characteristic way to communicate with the shoppers. The traders usually like to use handwriting and simple drawings to make price tag (Rivlin and González, 2017). This simple but special gesture is more humanized and makes it seem like some old habits in the market is always there.

Limitations and Consequences

While Kirkgate Market is keeping its traditional feature and generating its renewal plans, it is facing the limitation of the plan too.

Since Kirkgate Market is located in an old building with old infrastructure and design, and it is in the central place of the city, the rent is very high. The city council needs to spend a large amount of money to fix its roof leak problems, rotting problems and so on every year, which can make the rent higher. Many traders could not bear the high rent and had to leave the market (Gonzalez and Waley, 2013). The leaving of some shops leads to the loss of identity of Kirkgate Market, it is reducing the characteristic of the market, just like flowers fade.

Kirkgate Market is located in the heart of the city so it possesses significant potential for high real estate values (Gonzalez and Waley, 2013). Historically, this market has historically been a place that provides services to low-income populations. However, Kirkgate market is facing the pressure as the redevelopment project of the city brings more new shopping arcades to the city. These new shopping arcades improves the standards and gentrification of shopping places and becomes the challenges to Kirkgate market (Gonzalez and Waley, 2013).

As a central place unregulated by symbols, vendors in the market employ a variety of elements such as color, typography, imagery and layout to express themselves in decorating their stalls, displaying a diversity and creative freedom that is increasingly rare in modern marketplaces. However, with public spaces becoming more dominated by corporate and brand-driven aesthetics, the space for creative expression of individuals and small businesses is becoming constrained (Adami, 2020). How to maintain its unique characteristics amidst these evolving commercial trends is a question that Kirkgate market needs to consider.

When it comes to data, the most important first thing should be to clarify the definition of data that we have used in this study. In all current research, data are basically divided into two categories, one related to the data itself and the other related to computers. The former defines data as factual information used as a basis for reasoning, discussion, or computation (H. A. Gleason, Jr.), while the latter, in joint computer terminology, defines it as information that has been converted into a form that can be moved or processed efficiently. Or: information converted into binary digital form (Jack Vaughan). It is easy to see that, in any case, data is information of some kind. And this coincides with the meaning that will be adopted into this study.

references

Adami, E. 2020. Shaping public spaces from below: the vernacular semiotics of Leeds Kirkgate Market. Social semiotics. 30(1), pp.89–113.

Bail, C. 2014. The cultural environment: measuring culture with big data, Theory and society, 43(3/4), pp. 465-482.

Barnes, T. J. (2013). Big data, little history. Dialogues in Human Geography, 3(3), pp. 297-302. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820613514323

Beer, D. (2016). How should we do the history of Big Data? Big Data & Society, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716646135

Burkey, B. (2022). From Bricks to Clicks: How Digital Heritage Initiatives Create a New Ecosystem for Cultural Heritage and Collective Remembering. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 46(2), pp. 185-205. https://doi.org/10.1177/01968599211041112

Burkey, B. (2020). Repertoires of Remembering: A Conceptual Approach for Studying Memory Practices in the Digital Ecosystem. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 44(2), pp. 178-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859919852080

Burkey, B. (2019). Total Recall: How Cultural Heritage Communities Use Digital Initiatives and Platforms for Collective Remembering. Journal of Creative Communications, 14(3), pp. 235-253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258619868045

Crocker, J. W. (2022). Data-Becoming: History, Violence, and Justice. International Review of Qualitative Research, 14(4), pp. 631-648. https://doi.org/10.1177/19408447211049507

Diglin, G. (2014). Living the Orwellian Nightmare: New Media and Digital Dystopia. E-Learning and Digital Media, 11(6), pp. 608-618. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2014.11.6.608

Merriam-webster dictionary , about:data. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/data

Gonzalez, S. and Waley, P. 2013. Traditional Retail Markets: The New Gentrification Frontier? Antipode, 45(4), pp.965-983.

Newell, J. (2012). Old objects, new media: Historical collections, digitization and affect. Journal of Material Culture, 17(3), pp. 287-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183512453534

Rivlin, P. and González, S., 2017. Public markets: Spaces for sociability under threat?: The case of Leeds’ Kirkgate Market. In Contested Markets, Contested Cities, pp. 131-149.

TechTarget, definition of Data, by Jack Vaughan, available at: https://www.techtarget.com/searchdatamanagement/definition/data

Townsend, R.B. (2010) ‘How Is New Media Reshaping the Work of Historians?’, Perspectives on History, 48(8), pp. 31–36. Available at: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ahl&AN=55599098&site=ehost-live (Accessed: 27 April 2024).